|

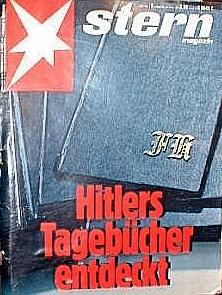

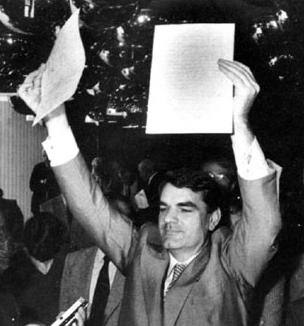

April 25, 1983. West Germany’s Stern magazine, expecting extrordinary demand, has distributed over two million copies of its latest issue. The cover story: “Hitler’s Diary Discovered.” The world’s media go gleefully along, with the London Sunday Times, the New York Times and Newsweek rushing their own stories to print. If the diaries were real, the excitement was certainly justified — but we know now that they were forgeries, and not particularly good ones at that. That they were accepted as true by eager press vultures and skeptical scholars alike goes to show that the success of a hoax or a fraud often has more to do with individual idiosyncracies, the social mood, and dumb luck than the careful cunning of the trickster. Over the two years before the first excerpts were published, Stern paid about ten million marks to a mysterious “Dr. Fischer” through a nazi-obsessed staff reporter, Gerd Heidemann (who was skimming the bulk of the money into his own accounts). Dr. Fischer was supposedly having the diaries smuggled in from East Germany, one at a time, hidden inside of pianos. Heidemann had gone quite over the edge, insisting that he was in communication with long-dead Nazi brass and entertaining some prominent actually-living veterans of the Third Reich on Hermann Göring’s yacht, which Heidemann had restored at considerable expense. Heidemann was easy to fool, and in fact continued to believe that the diaries were genuine long after the fraud was uncovered. He played the part of the primary rube in this story, but he also provided the majority of the energy behind the hoax, and evidence for the hypothesis that in people honesty and foolability are found in inverse proportion. (Usually worded: “you can’t cheat an honest man.”) “Dr. Fischer” was actually Konrad Kujau, who’d managed to make a good living for himself by forging hand-written Mein Kampf manuscripts and paintings “by Hitler” for Heidemann and other gullible collectors. Almost a quarter of the more than 700 artworks represented in Billy Price’s 1983 book Adolf Hitler: The Unknown Artist were actually Kujau forgeries. Kujau’s customers were more eager to own a piece of the Nazi past than they were to verify the authenticity of their purchases, so Kujau wasn’t particularly cautious about accuracy. The diaries themselves were full of flaws:

The success of the fraud had less to do with the technical sophistication of the forgery than the combined and contagious gullibility of many people. The more money Stern spent, the more convinced they became of the authenticity of the diaries. The more Heidemann displayed his obsessive and gullible nazi fixation, the more people assumed that someone else must be keeping him on a short leash. Handwriting experts called in to judge samples of the writing in the diaries announced that the writing perfectly matched other samples of Hitler’s script — what they didn’t know was that the comparison samples had also been forged by Kujau! One of the most prominent oopses came from Hugh Trevor-Roper, Oxford fellow, Cambridge Master, and author of The Last Days of Hitler (based on his work with British intelligence). Writing for the London Times about the discovery of the diaries and numerous other forged Hitler writings, shortly before the first excerpts were published in Stern, he wrote:

One of the earliest and most vocal critics of the diaries’ authenticity was maverick historian David Irving. Irving makes much of this on his web site, but fails to mention that at the last minute, shortly before forensic tests proved the diaries to be fakes, he switched positions and announced that he, too, believed that they were genuine. Here’s one of those ironies that makes me wonder if the hoax doesn’t go all the way to the Top: A fellow named Magnus Linklater assembled the London Sunday Times’ dizzy coverage of the diaries. A little over a decade earlier, Linklater had been a member of the team that wrote Hoax, a study of the fake Howard Hughes autobiography that Clifford Irving sold to Life magazine. Linklater smelled something rotten in the Hitler diaries, but even with his magnified insight into an eerily similar forgery, he was unable to resist the momentum that the diaries had behind them. Two years after the fraud was uncovered, Kujau and Heidemann were each sentenced to four and a half years in prison. Kujau later leveraged his fame into an above-board (if somewhat ‘novelty’-oriented) artist’s career, and was selling his acknowledged forgeries/copies of the masters up to his death in September, 2000. Heidemann was last spotted telling a researcher that he’d had “enough of Nazi shit.” The news media have made no sign of attempting to mend their ways. |

Stern’s coverage  Konrad Kujau  Gerd Heidemann  David Irving

|

|

|

| snig·gle (v) — To fish for eels by thrusting a baited hook into their hiding places. |